Nicola Tesla, the great inventor, believed that the newly discovered radio could be used to contact the spirits. Over many years, he and other famous inventors,including Marconi and Edison, searched for a way to “tune” their signals, upgrade their circuits, or otherwise make changes to achieve the new, fantastic purpose.

They were not completely successful with their intent, although Edison described some strange signals picked up by some of his apparatus. But the basic question remained, “Can electronics be used to contact spirits?”

The movie “The Grass Harp” opened the door to a relatively unknown phenomenon that can be a key to the idea of an apparatus to communicate with the dead. The movie tells the history of a little girl who could hear the voices of the dead in plant leaves shaken by the wind.

This historical outline explores a real phenomenon that is of increasing interest now that electronic resources are more readily available.

Instrumental Transcommunication

Instrumental transcommunication (ITC) is the name of this new para-science, with many sites in the Internet exploring the subject..

The basic idea is based on enlisting the aid of electronic devices to record voices from the beyond that appear when the sound of the leaves being shaken by the wind (white noise) are simulated by electronic circuits.

The important concept to keep in mind is that “The Grass Harp” explores a real fact and that experiments for hearing the dead can be conducted by anyone, including you, using common electronic circuits and equipment.

The age for this interesting research began when the electronic voice phenomenon (EVP) was discovered. The EVP is part of man’s endeavor to establish contact with dead or other dimensions’ beings using electronic instruments.

The discovery was made in 1959 by Friedrich Jiingerson, a Swedish researcher, and it started with a wave of interest in this field. Jungerson was using a common tape recorder to record birds’ songs when he discovered mysterious voices in the recordings.

Mixed with the background sound (the wind shaking leaves as in “The Grass Harp”), it was possible to hear conversations of people who were not visible in the place where the recordings were made, and there were also other mysterious sounds.

The electronic voices were thought to be associated with beings who lived many years before in that place, or with beings of other dimensions.

The basic idea is that the background noise acts as a carrier or support and can be modulated by any other kind of signal-not necessarily electric fields (or energies, as commonly termed by researchers in this field) that are present in free space.

Without background noise, the signals are too weak to be detectable, but, in presence of a noise, their levels increase beyond the threshold of detection and become clear-sometimes loud.

This phenomenon, also called stochastic resonance, is well known in physics and telecommunications.

Stochastic Resonance

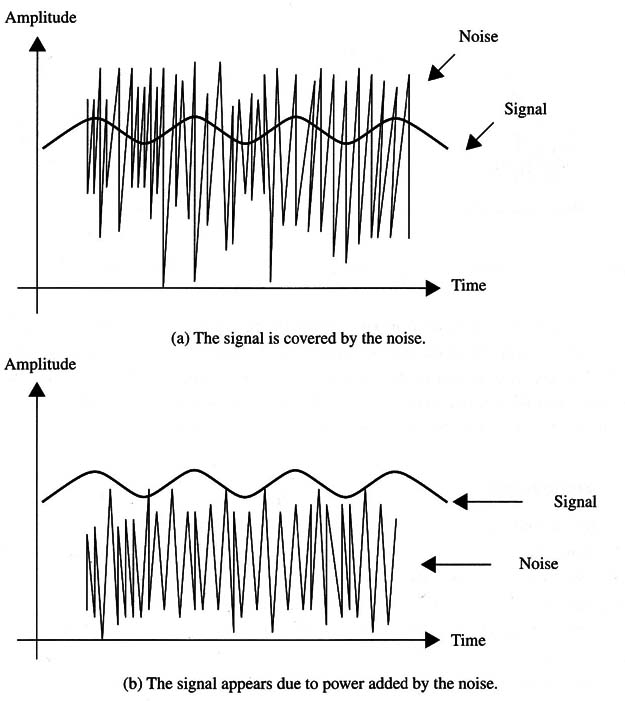

Stochastic resonance occurs when a modulated signal that is too weak to be heard or otherwise detected under normal conditions becomes detectable due to a resonance phenomenon produced between this weak deterministic signal and the signal with no definite frequency-the stochastic noise. Figure 1 shows what happens.

The weak signal is covered by the noise under normal conditions and is not detectable. But the same noise can be added to the weak signal, increasing its amplitude. In such a case, the undetectable signal rises to a detectable level.

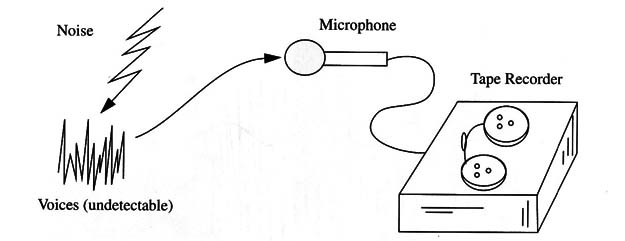

In the case of the experiment made by Jiingerson, the background noise (wind shaking the leaves) provided exactly the support necessary to make the undetectable voices become detectable and appear when the tape was heard, as Fig. 2 suggests.

Researchers can’t explain why the voices are not audible in the ambient where they are produced but appear in the playback. Possibly the presence of an electric field is necessary for the manifestation of this phenomenon. This also would explain the apparent need for some kind of recording instrument in all the experiments involving EVP.

After J fingerson’s discovery, many other researchers began with a series of experiments, trying to pick up voices from the beyond. They first used common tape recorders as J iingerson did. Later, other, more complex devices were implemented, including computers and TVs.

The most important of these researchers was certainly Dr. Konstantin Raudive. He died in 1974 but left a number of works aimed at convincing humans that contact between the dead and the living is possible.

Dr. Raudive used not only common recorders to make his experiments but the complete range of equipment with which the principle of the stochastic resonance could be applied. Cassette tape recorders, video recorders, radio receivers, CD players, and even computers have been used in the experiments, beginning a new line of research that now also involves images.

To produce the phenomenon of stochastic resonance, it is necessary to use some form of support or carrier to increase the amplitude of the signal to be detected. The experiments and devices used in transcommunications are all based on some kind of a noise source, with the most common being white noise, although other types of noise (e.g., pink noise) can be used.

White Noise

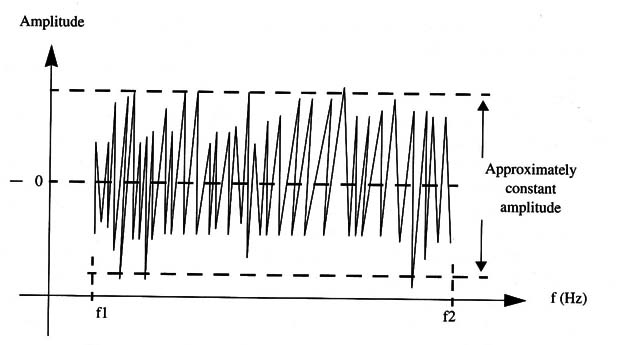

Physicists define white noise as a random sound within prescribed volume and tonal parameters. A more complex way to define white noise is as a signal with equal power per frequency unit (hertz) over a specified frequency band.

Another, more technical, definition is, “White noise is noise with an autocorrelation function zero everywhere but at 0, also called Johnson noise. It has a constant frequency spectrum.”

The main sources of natural background noise are molecular agitation of matter via temperature changes, and natural electric discharges in the atmosphere. When we put a shell over our ear to hear “sea” noise, we are adding an acoustic amplifier to our natural hearing organs. The shell increases the white noise level produced by the thermal agitation of the air molecules to a value above the audible threshold. This is an audible white noise.

The same concept can be applied to electric signals spreading the frequency band to infinite values. This means that high-frequency circuits such as those found in radios can also be used to perform experiments in transcommunication (see Fig. 3).

The natural atmospheric discharges fill the electromagnetic spectrum with white noise that appears when we tune a radio receiver between stations as audible white noise (also known as hiss) or in a TV as visible “snow” when it is tuned to a free channel.

Many electronic components (e.g., resistors, diodes, transistors) can be used to produce white noise covering a large band of frequencies. These devices will be used as the basis of white noise generators in many of our projects.

Pink Noise

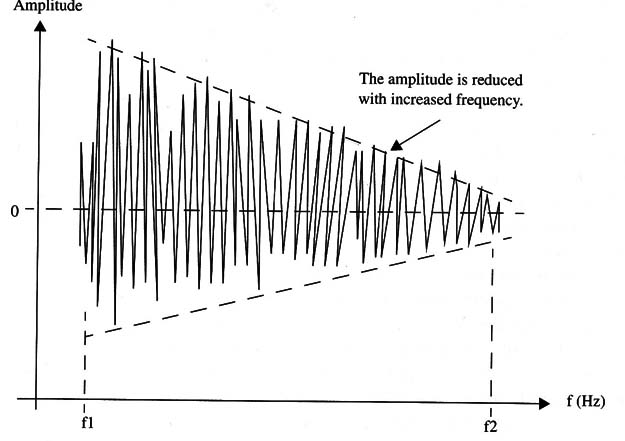

Another kind of noise that can be used in projects involving transcornmunication is pink noise. The difference is that pink noise has an amplitude that decreases along the frequency spectrum as shown in Fig. 4.

Noise can also be present in imaging processes. The snowy image on a TV is the result of noise present in the received signal or in the circuit of the TV set.

The noise in a image can also be used in many experiments to detect “images from the beyond.”

In the 1970s, the American pioneer George W. Meek began researching electronic voice phenomena with a new aim: to achieve prolonged two-way communication rather than simply receiving short and isolated phrases as found in previous experiments.

He created a device, named the Spiricon, designed to maintain communication with the place from whence the voices were coming.

He believed that the voices “came from beings residing in astral planes.” The apparatus was basically a high-frequency oscillator, with the first version operating at 300 MHZ and later versions at 1,200 MHZ. The signal was used to fill the experiment room and was detected by a special circuit (a demodulator).

The results showed that a solution to the problem did not lie in using high-frequency signals.

William J. O’Neil obtained the best results by lowering the frequencies used in the experiments. The new apparatus operated at 29 MHz.

Shortly afterward, the next generation of researchers appeared, and in 1982 in event at the National Press Club in Washington, DC, attracted more than 50 reporters and researchers from many countries. Immediately, the news about the experiments spread all over the world, and a host of researchers began their experiments in countries such as Brazil and Russia, and throughout Europe and Asia.

Names including the German psychic Klaus Schreiber; Brazilians Max Berezovsky, Sonia Rinaldi, Hilda Hilst, and Ernani Guimaraes; and many others made significant contributions and must be included among the important researchers in this field.

The author, in several contacts with Dr. Max Berezovsky, learned much about the necessary equipment to undertake these experiments, creating many of the circuits found in this section from his suggestions.

We must also include the Luxembourg team, Jules and Maggie Harseh-Fishback, in our list of researchers who reported positive results in experiments involving ITC, and Ken Webster, who described how he received messages from the “other side” on his computer.

It is also important to remember that the first attempt in this field seems to be that of Jonathan Koons, in 1852, but the blueprints of his “machine” have never been found.

Sometime after the above-mentioned experiments were conducted, the name instrumental transcommunication (ITC) was first suggested for this parascience.

The origin of the “voices” or “images” is an interesting point of discussion. As described above, the assumption from which the first researchers began their studies was that the messages (voices or/and images) come from the dead, but other possibilities soon had to be considered.

One of them is that the voices came from other-dimensional beings. These beings would live in a “parallel universe” with several degrees or levels or planes (astral planes).

The contact with us, according to the researchers, is constant but sometimes not perceived by us. “They are here, but we can’t see them,” explain the researchers. Many believe that they act as “angels,” protecting or acting on our lives and destinations without our observation.

Another theory says that the messages are generated inside our brain, and the background noise could trigger some internal feedback processes, making it detectable.

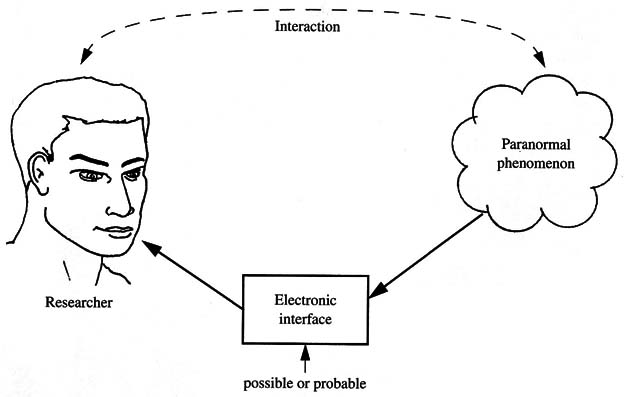

Subconscious minds or even external signals can be transferred to the equipment and detected, appearing superimposed to the sounds and images, giving to the persons the impression that the voices came from an external source and not from their brain, as suggested in Fig. 5.

In this case, the brain will act as an “interface,” transferring some kind of unknown and undetectable information from somewhere to an electronic device, making it visible or audible, or placing it on a magnetic tape or other medium such as a computer printer.

This could explain why experts recommend that experimenters be in a special mind state when making these experiments!

Notice that this cannot be attributed to a psychic disorder in which the sounds are imagined by one person. The noise will help the brain to “tune” the information coming from outside and “add” them to the ambient noise in such a manner that all persons near the “receiver” can also hear them.

There are also people who believe that the messages come from a universal “data file” where all we say and do is stored and can be accessed anytime thereafter.

The electronic equipment is used as a channel or medium to tune in those data, although the use of recorders in this manner precludes the possibility of choosing exactly the information we want.

It is like a situation in which we have discovered the radio receiver but not the way to tune to a desired station. What we pick up and when is not totally controlled yet. Researchers are still trying to find how to do that.

It is not for the author to decide what is the real or the correct answer to all these issues, as the researchers have reached no conclusions, and many doubts and questions about this subject are still unanswered. As in all science, there is much noise created between people who seek reality and those who want to use ITC for nonscientific purposes.

Serious research will separate the noise from the signal-we hope.

Because this section is directed toward individuals who want to conduct practical experiments using available equipment and circuits, rather than constructing advanced theories, considerations about the nature of the phenomenon are not included.

For present purposes, we can only suggest experiments and equipment based on existing theories and the work of well known researchers. There are also many sites on the Internet where the reader can find much useful information, not only about the researchers but also about their works.

Consequently, a reader who is attracted to this unusual aspect of electronics and wants to make his own experiments will find some practical circuits herein.